Whilst the late nineties had proved a fruitful time for television and church backed projects, by the turn of the century the major studios had considered the Bible film genre was dead. The experimental period had provided some success with smaller projects, but the vitriol, and indeed threat to life, faced by the makers of

Last Temptation of Christ had led them to the conclusion that any similar projects were extremely risky; if anything the Christian right which mobilised itself in response to the film had grown in size, influence and power. Yet at the same time, with falling church attendances and subject matter so significantly at odds with the zeitgeist of the new millennium, it seemed unlikely that a Biblical Epic could find a large enough audience to cover its production costs, let alone prove profitable.

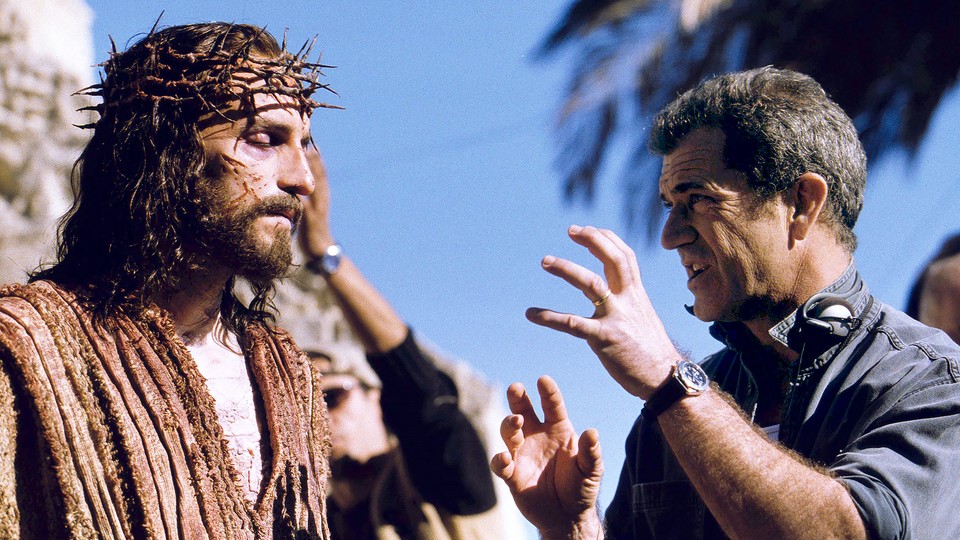

Such was the degree of scepticism that even a major Hollywood star, who had enjoyed success with an historical epic at the box office and with critics, was unable to find backing for film about the death of Jesus. Part of this was perhaps due to the uncompromising vision of Gibson's film. Rather than a family friendly, bland Jesus film such as

The Greatest Story Ever Told it would be ultra violent and in a foreign language. If Hollywood Execs had even considered the possibilities for a moment, they would have swiftly dismissed the possibility of a Christian audience turning up

en masse for a violent, R-rated film.

Hindsight is a wonderful thing, of course, and we now all know the end of the story. Rejected by every major studio, and no doubt a few minor ones along the way, Gibson decided to fund the project himself. He spun the studios rejection into a David and Goliath story, worked tirelessly to pitch it to church audiences and gain the support of their leaders, and, as a result, the film made a huge profit. The resulting success spawned a myriad of new Biblical Epics, both at the cinema and on television, but, as with the supposed Golden Era, whilst some proved successful many have failed to find an audience.

In many cases this is because the studios that failed to predict

The Passion's success, continued to mis-diagnose the reasons why it proved successful. Much of the failure of the subsequent films suggests that those responsible for green-lighting these projects had drawn the wrong conclusions. I want to highlight some (and I stress "some") of the reasons why

The Passion did well and perhaps why subsequent releases did not.

Fragmentation and Tribal Identities

If 2016 taught us anything (and it seems clear that for many people it did not) it's that we're living in increasingly factionalised times, times where the different factions are not only becoming more and more distinct from those in other factions, but where each is starting to get caught in a self-reinforcing bubble, where the stories, news, beliefs and practice of those within one bubble bear very little relation to those of other factions.

For decades filmmakers and promoters tried to try and hold the different factions together in the hope of appealing to enough of them to make their product worthwhile. What Gibson did however was to ignore very large sectors of the market in order to focus more squarely on other factions. So very few of the middle class, city-dwelling, younger audience have seen Gibson's film. Indeed I get the impression that the majority look at it with disdain. But for practising Christians from more conservative households, Gibson's uncompromising vision was exactly what they felt they had not been served by the Hollywood system.

One of Gibson's key approaches, then, was not to bother to court the whole population, but to focus on the conservative, church-going population. He figured if he could get them on side in sufficiently large numbers then he didn't need to attract those from ourside that demographic. This was the basket into which he put all his eggs, and it paid off.

Grassroots, word of mouth and social media

Gibson also rejected the more traditional top-down marketing approach of spending a huge amount in buying premium media advertising space and reinforcing the message again and again. Instead he practically reinvented the grassroots campaign. Focusing in on his demographic he realised that church leaders held the key. By both dazzling them with his star power (humbly attending their conferences), focusing on their common ground (e.g. a "manly" Jesus, a traditional version of the story), building a strongly persausive case for the areas where their preferences may have differed initially (e.g. using original languages) and speaking their language ("The Holy Ghost was working through me on this film...I was just directing traffic."), he got church leaders on board. Not only were they interested in his project, but they were fully on board, convinced that this created an opportunity to forward their agenda ("an evangelistic opportunity"). Ultimately they were so convinced that not only did they encourage, and in some cases direct, their congregations to buy tickets for the film (thus doing the job of marketing) they also booked out cinemas and sold tickets

en masse (thus also doing the job of sales).

Whist this was before the advent of social media as we know it today (before the emergence of Facebook and Twitter) there was still an enormous amount of sharing on websites, blogs and discussion fora. For example, the

Arts and Faith forum where I was active at the time had both a -pre-release thread and a post-release thread adding up to over 1150 posts between them. And the film's marketing team didn't need to buy advertising space in the various glossy Christian magazines, as they were all covering the film in their features sections. It was, after all, what everyone was talking about.

Subsequent Bible filmmakers have also tried to promote their films by these routes, by emulating much of what Gibson did. Whilst it was unlikely that any film would reproduce

The Passion's success, there have been very few real successes and it is notable that when the two big Bible films of 2014 were released this strategy was relegated to being only a minor player. Part of this is due to audience fatigue - as the novelty of being courted wore off each new appeal generated less interest - but also a lot of the subsequent pitches to churches failed to capture what Gibson brought. Yes some of that was the kind of star power that very few could bring, but there were other aspects of the appeal to churches that were not picked up on that might have been easier to reproduce and I want to look at one or two of those now.

Muscular Christianity

As alluded to above, Gibson's Jesus was a "manly" Jesus. In the run up to the film's release he talked several times about the weaknesses of previous silver-screen Christs and it was not hard to imagine that he was often referring to the slender Robert Powell in

Jesus of Nazareth (see the various quotes in my old piece "

Film: A New Passion"). Instead Gibson produced the most violent Jesus film ever made and presented his hero as a figure who was not unlike the Martin Riggs character that Gibson played in

Lethal Weapon (1987). Like Riggs Gibson's Jesus could suffer immense pain and yet instead of giving up would come back for more (such as the flagellation scene where Jesus defiantly drags himself to his feet after an already heavy beating). Gibson's William Wallace also comes to mind.

What's interesting about this is that certain sections of the church have traditionally protested against sex and violence on our screens. There's an argument to say that these are not all the same groups of people, and certainly there's some truth in that. At the same time think there are many who would hold to that argument in general but would make exceptions in certain cases such as this.

Later Bible films, like

The Nativity Story (2006) reverted to the model of Bible Films as family friendly fare. It flopped. In contrast one of the few productions to take a more violent approach to the scriptures, 2013's

The Bible proved more successful. It's perhaps an uncomfortable conclusion but, for me, the

Passion's violence was part of the reason it was so successful with the Christian market. That might seem like a shocking thing to say, and is perhaps an uncomfortable opinion, yet the filmmakers could not have been more clear about the film's level of violence. "By the time [audiences] get to the crucifixion scene, I believe there will be many who can't take it and will have to walk out - I guarantee it" actor Jim Caviezel said as part of the film's promotion and there is a profusion of similar quotes.

1 Indeed most of the claims about the film's historical accuracy were really claims about the film's 'accurate' depiction of the violence to which Jesus was subjected.

This was a message that strong appealed to many Christians. Fed up of being seem as effeminate for following Jesus they yearned for a films such as Gibson's which reaffirmed that following Christ was not a slur on one's manhood. This leads nicely into the next reason for the film's success.

The Religious Right's Persecution Complex

For years now many parts of evangelical Christianity - on both sides of the Atlantic - have had something of a persecution complex. This seems to exist in spite of the fact that many Christians in other parts of the world are actually being persecuted and tortured for their faith. So the incredibly rare stories of staff being asked not to wear religious symbols, or not being allowed to discriminate on the basis of sexuality have been used to stir up tremendous feeling in the UK. In the US there's been no shortage of claims that Christianity is under attack. It's no coincidence that the most visited article on my whole blog is the one that explains that the rumours about a film being made about a gay Jesus are false.

To an audience soaked in this mindset Gibson's tale of his struggle to find funding for his pet project struck a familiar chord. How typical of the liberal elitist Hollywood to reject such a film, and so it quickly rallied people to Gibson's "cause". A similar things happened recently with Donald Trump's ascent to the presidency. Trump played the card of Christian persecution and found an evangelical base that voted 81% in his favour. He continues to claim he is being persecuted even though he is now the most powerful man in the world.

By pitting himself as some sort of David against an anti-Christian Hollywood Goliath, Gibson grew a huge base of support all who shared his passion to see a decent portrayal of Jesus to supplant the weak film Christs of

King of Kings and

Jesus Christ, Superstar. No-one really stopped to ask what kind of David had enough personal wealth to be able to sink £25 million dollars into making the film on their own. Nor what he would do with all the profit if it proved to be successful.

What is most troubling about this reason behind the film's success is not the opposition Gibson faced initially, when trying to make the film, but the way he handled the questions people raised about the content of the film. Many, on hearing that Gibson had used Katherine Emmerich's ant-Semitic "Dolorous Passion of Our Lord Jesus Christ" as one of his major sources, were concerned that the film too would be anti-Semitic. Instead of listening to these voices, seeking to learn from them, act, amend any content that he'd not previously realised would prove troubling and promote the film with even greater endorsement, he chose instead to go to war. He again played the persecution card, marking out those who questioned the film's potential for anti-Semitism as a powerful enemy when they lacked even a fraction of the resources he possessed. Sadly this further rallied many parts of the church to his defence, many of whom failed even to see the significant difference between the words in scripture and the interpretation of those words in a film. Buying a ticket for the film became seen as a way of supporting Gibson, and by extension the Bible, against those who would criticise it.

Supernatural Endorsement

One other thing which is notable about the marketing of this film, which has tended to be absent in later biblical films is the way Gibson used different forms of supernatural endorsement for his film. This is in fact nothing new and goes back to several of the Jesus films from the silent era. DeMille for example used some of the self-same methods. There are at least four different strands here.

Firstly there are the claims for inspiration. The most famous is Gibson's claim "The Holy Ghost was working through me on this film, and I was just directing traffic"

2. Even at the time I remember there being debate about whether this was a 'pitch' or Gibson's genuine belief (and perhaps it was both), but certainly it had the effect of persuading people that it was something they should go and see. Enough people believed the film was, in some way God inspired.

Secondly there were the accounts of miracles as well as what will have sounded, to many, as attacks from the enemy. The most memorable of these are the claims that twice people were struck by lightning during the filming of the crucifixion (including leading actor Jim Caviezel). In previous generations that might have been seen as God being against the film rather than in favour of it, but here the fact that one of them "just got up and walked away" was taken as evidence that God was protecting the cast and crew.

3. In the same piece Gibson also talked about "people being healed of diseases".

4

The third way, which also crops up in on of the pieces that was circulated long before the film's release, is the mention of conversions during filming. "Everyone who worked on this movie was changed. There were agnostics and Muslims on set converting to Christianity".

5 this ties in with Gibson's hope that the film would have the "power to evangelise"

6. This later theme was picked up by church leaders who began to market the film, on Gibson's behalf, as an evangelistic tool.

Lastly there is that infamous almost-endorsement by the Pope. Whether or not the Pope really said "It is as it was" and the story behind the quotes hasty retraction is irrelevant, that became the story and the endorsement of it from the church's high office. Even though the majority of those buying tickets may not have been Roman Catholics, the words attributed to the Pope became gospel and even if he didn't actually say them, his team weren't fighting too desperately to retract them. This combined with Gibson's unsubstantiated claims for historical accuracy gave the film further credibility - a crucial criterion for many evangelicals.

In addition to these three factors there are also three further lessons that could be picked up from

The Passion's success.

The Growing Christian Audience

Gibson's genius was to realise that there was a growing Christian audience out there who would respond positively to the right product. This audience had not had a great deal of specifically tailored quality content in the years leading up to

The Passion's release and it's questionable as to whether they've had a great deal of it since. America's culture wars and the emergence of a more vocal form of Christianity, prepared to show its loyalty to the brand had created a growing, and in some ways new, market. Whilst many of the films that have subsequently sought to exploit that market have failed, a greater number have succeeded than ever did before.

Diminishing Influence of (Liberal) Experts

One of the quotes that so typified the Brexit debate in the UK was the pronouncement of the (then) Lord Chancellor Michael Gove that the "people in this country have had enough of experts". With similar sentiments being felt on the other side of the Atlantic as well it reminds me of how many people spoke out about the more problematic aspects of the film (the excessive violence, the anti-Semitism, etc.) without causing any change in the final film, or any significant impact on its box office success. The not-at-that-point disgraced Ted Haggard's claim that the film "conveys, more accurately than any other film, who Jesus was"

7 was repeated far more times than those of biblical scholars, with their expert knowledge of the gospels and the world in which Jesus lived and ministered. Many objections by those who had a greater knowledge of the relevant issues were waved away in the rush to endorse such a powerful evangelistic tool. The article I had written for a Christian magazine weighing the pros and cons of the forthcoming film (available

here), for example, was dropped at the last minute for one talking about how it was going to usher thousands of new converts to Christianity. Not that I'm bitter (I am).

Diminishing Influence of Film Critics

Not unrelated to the above, a pattern has emerged subsequently in the Christian press surrounding the release of major new Bible films. When such a film is released numerous Christian magazines turn not to their in-house film critic, or even to an experienced Christian film critic, but to a popular/influential leader and/or speaker instead who will give their opinions on the likelihood of the film "reaching" those outside the church or how the film coincides with their own personal idea of what Jesus was like.

But this is not just a problem with the church. In the decade and a bit since the release of the film it has become increasingly clear that the majority of people don't really care, or even agree with, what film critics say. Few, if any, of the top performing films at the box office will appear on critics' end of year lists and whilst Oscar nominations will boost a film's earnings, they are hardly a predictor for financial success (and many critics look down on the Oscar nominations which the general population often considers too highbrow). Back in early 2004 critics were not exactly expecting great things from

The Passion. The studios valued such opinions then and perhaps even shared them. Today they would be unlikely to take them seriously. Film critics no longer have the power to derail a movie let alone one with the power to evangelise.

1 - Holly McClure - New York Daily News - A very violent 'Passion' (reproduced here). January 26, 2003.

2 - Kamon Simpson - Colorado Springs Gazette - "Mel Gibson brings movie to city's church leaders" - June 28, 2003

3 - Holly McClure - New York Daily News - A very violent 'Passion' (reproduced here). January 26, 2003.

4 - Holly McClure - ibid.

5 - Kamon Simpson - Colorado Springs Gazette - "Mel Gibson brings movie to city's church leaders" - June 28, 2003

6 - Kamon Simpson - ibid.

7 - Kamon Simpson - ibid.Labels: Passion of the Christ

.jpg)